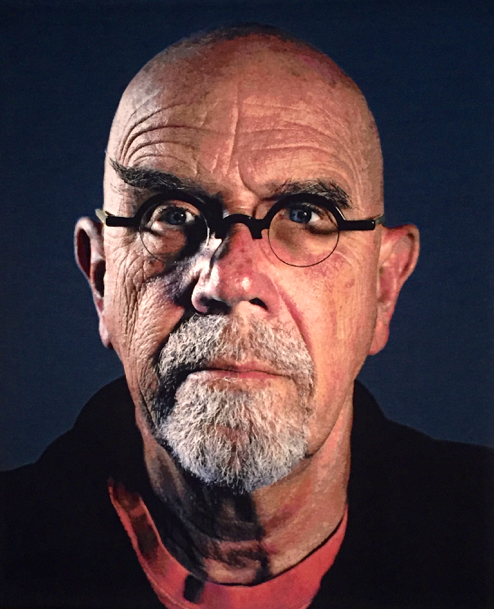

It is hard to imagine two contemporary artists more different than Chuck Close and Tony Foster. Close is a local guy (born in Monroe, WA) who’s become an international superstar known for his tightly focused, hyper-realistic portraits and self-portraits in a variety of mediums. Foster is a quiet Englishman who searches out remote and often endangered landscapes on his “wilderness journeys,” and records them in large complex watercolor paintings using only a pencil and small watercolor paint box.

In the last two weeks I’ve had the good fortune to see the work of both artists in near perfect settings. The Schack Art Center, in Everett, Washington is an unlikely location for an exhibition by a world renown artist like Chuck Close, except for the fact he grew up there and maintains strong ties to the community. The exhibit, which closes tomorrow (September 5th) is a stunning and comprehensive look at his work as a printmaker with detailed descriptions of various processes and collaborators.

I knew that Close had suffered a devastating spinal artery collapse in 1988 that left him a quadriplegic, and I knew that he had regained some mobility through rehabilitation, but I was astonished to discover that he also suffers from a condition known as prosopagnosia, aka facial blindness, a condition that prevents him from recognizing faces. He has said that he might have dinner with a person one night and not recognize him the next day. These obstacles seem almost impossible to overcome but for an artist known for his facial portraits the achievement seems incomprehensible. Nevertheless, he continues to draw, paint, print and make tapestries with an output that would shame most artists.

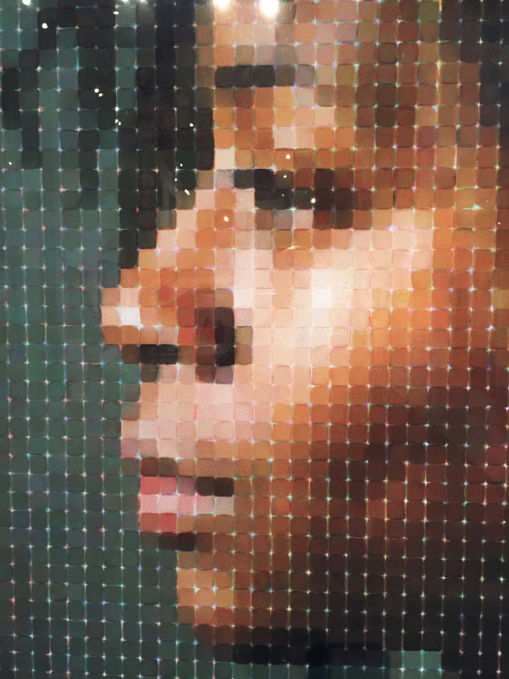

Working on a pixel-like grid, he draws, paints, or etches the portrait, small square by small square, until the grid is filled in and the portrait complete.

Or,

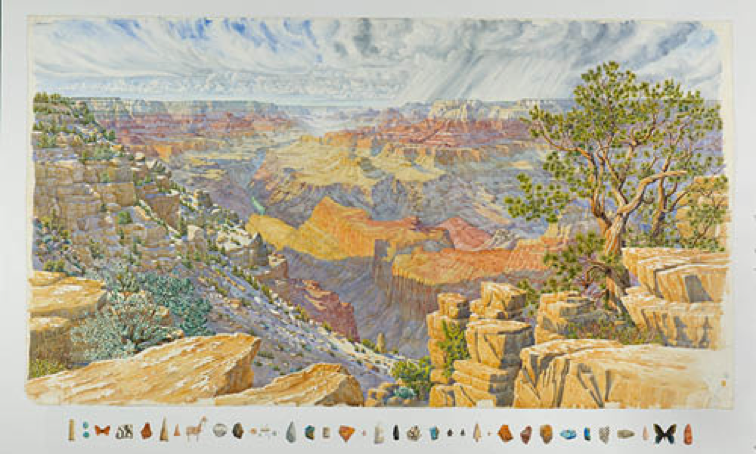

Tony Foster, is just as meticulous, but worlds apart in technique. Close has married the science of printmaking to the creative generator in his head and produced a stunning array of artistic and technically complex portraits. Tony’s creative journey is more geographic and his workmanship simpler in an effort to capture, convey, and preserve the magic and grand scale of the physical world on a simple piece of paper.

I was with Tony and a group of friends on an 18-day raft trip through the Grand Canyon in 1999. At the end of every day, as we were setting up camp and preparing for dinner, Tony would strap on a backpack with his tools – folding easel, aluminum tube of rolled watercolor paper, pencils and paint box – and strike out in search for a good vantage point near the camp. Then, for two or three hours he would sketch the canyon and fill in the outlines, capturing the essential colors of the landscape with his small box of paints, in order to freeze the scene in his mind enough to complete the painting later in his Cornwall studio. On our trip, he was able to develop 16 large (up to 7’ x 4’) paintings which the Denver Art Museum purchased as a complete set and record of the trip.

As an avowed conservationist, Tony is motivated to preserve and protect the wild environments he records in his work, The paintings themselves include journal-like notes about the site, problems encountered, and artifacts found in order to add to the viewer’s understanding of the location – sand, rocks, wood pieces, grasses, etc. – all incorporated into the artwork.

Unlike Close who works almost exclusively from photographs, Tony never uses photographs. He works strictly from memory to complete the work laid down on-site in the wilderness.

Recently, Jane Woodward, a longtime admirer and collector of Tony’s work, underwrote the renovation of a large industrial space in Palo Alto, California and the creation of The Foster Foundation where visitors can see and appreciate the range of his watercolor “journeys” and be inspired to connect with the wilderness. Located at 940 Commercial Avenue, the foundation has brought together a wide sampling of Tony’s work in a space where the “journeys” can be seen as a continuum. Over the past 30 years, those “journeys” have taken him from the American Southwest to Europe, Central and South America, Hawaii, Alaska, the Caribbean, Greenland, Nepal, and Borneo. This remarkable and ever changing collection in Palo Alto can be viewed by appointment. To arrange a visit contact the staff through the website www.thefoster.org. I found them to be generous with their time and extremely knowledgeable about the art.

Chuck Close and Tony Foster are close to the same age – both in their 70s now – and both still highly productive. I’ve always believed that engagement is the key to longevity – as long as the little green hands of fate don’t intervene and throw you a bean ball. I highly recommend both exhibits. If you’re in the Palo Alto area, give the foundation a call and arrange a viewing of Tony’s work. If you’re anywhere near a Chuck Close exhibit don’t miss it. The show in Everett is exceptional. I don’t know if it will travel to other museums, but most major museums, including the Seattle Art Museum, have examples of his work. I hope you get to see this one, but, if not, don’t pass up a chance to see his work in another setting.

Check this out for an example of Close’s creative dexterity. The distorted portrait on the table is reflected as a clear picture on the polished stainless column in the center of the display.

Hi Jack,

Thank you for your thoughtful and insightful blog.

I am delighted that you engaged so closely with my work, and as an admirer of Close, I am flattered that you connected us through your writing.

My new show , which I think will blow your socks off, opens in Palo Alto in early March.

I hope you will be there so that we can reconnect.

Best,

Tony