If you’re here, reading this article, your luck is probably holding, but not everyone is so fortunate. Have you met or do you know a refugee?

Sure, the guy who mows your lawn or the woman who changes your sheets may be an undocumented worker – an “illegal” – but they’re probably not refugees. Neither are the guys who hang out in the Home Depot parking lot looking for odd jobs or the dishwasher at your local Mexican restaurant, but there are real refugees among us; Iraqi and Afghan interpreters who helped America fight its Middle Eastern wars, people from Honduras who fled murderous death squads, and girls from Asia or Central America who escaped their human traffickers. I count several Vietnamese who fled their country after the fall of Saigon as friends. These are all people who meet or met the definition of “refugee,” but today I’m thinking about the fresh-in-their-skins variety like those fleeing Myanmar, Syria, or Afghanistan–people on the run without homes to go back to. Up to the minute refugees.

Here’s where the question of luck comes in; with these people in mind it’s heartbreaking to reflect on the importance of luck in personal destiny. Accidents of birth. Genetic roulette. Geography. Tribal conflict. Racism. Sexism. Privilege. Despotism. War. Gun violence. Mental illness. Luck plays a role in everything from the micro to the macro – for refugees.

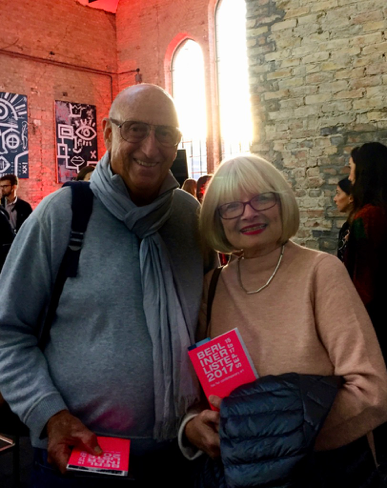

In September I had a miraculous experience. As Marilynn and I were descending a stairway leaving an art exhibition in East Berlin, I ran into a German friend I hadn’t seen in thirty years. Of the 3.7 million people who live in Berlin I happened to cross paths with her. An instance of the good kind of luck. Thirty years ago, when we lived and worked in West Berlin, we wouldn’t have been able to attend an art event in East Berlin, but in 2017 I was there and so was she.

Perhaps more miraculous than the unexpected encounter with Claudia was the fact that she was with a young Syrian refugee named Mohammad (aka Med). She introduced us. She and I talked briefly and agreed to catch up with each other the following week.

Thirty years ago, Med hadn’t been born. Thirty years ago, Syria was at peace. Today, Syria is a bombed-out shell and 26-year-old Mohammad “Med” Malandi, is a displaced refugee struggling to make a life for himself in Berlin. Bad luck as personal destiny.

The year 2011 changed everything in the Middle East. The “Arab Spring” swept across countries bordering the eastern Mediterranean – Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, Bahrain, and Syria. Revolution was in the air. Oppressed populations rose up to confront their oppressors. The hope that drove those uprisings has evaporated and countries that fell under their spell are, for the most part, worse off than they were before. That’s how Med Malandi became a haunting presence in my life.

This is Med’s self-portrait. He was always interested in art, but the onset of Syrian civil war turned him into a political cartoonist?

I need to tell you Med’s story, because remarkable as it is it transcends the personal and highlights what may be the biggest problem the world will face in the next decade. Bigger than the nuclear standoffs with North Korea and Iran. Certainly bigger than Russian interference in American elections. Even bigger than climate change.

And, speaking of climate, let’s start Med’s story today and work our way back. At this very minute, 11 pm on November 28th, 2017, it’s 41°F in Berlin. The forecast says it will be 31°F by 8 am. Med lives in an old art deco house on the outskirts of town but the house has no heating. His lease runs out in a few days and there is almost nothing available in his price range. The influx of refugees has pushed rents to unsustainable levels. Claudia will let him stay with her for a short while. She’s remarkable in her devotion to Med and the other refugee families she supports. She’s told me how much she enjoys Med’s company and what a good cook he is, but he needs a permanent place.

His journey to Berlin began two and a half years ago when he left his home and family in Idleb, a small agricultural community, 40 miles southwest of Aleppo. His parents, an educator and a housewife, chose to stay in Syria despite the fact that Idleb has been the sight of a seesaw battle between Assad’s government troops and the rebel alliance called the Army of Conquest (a loose coalition of Al-Nusra and Al Qaeda factions) mixed in with some irregular ISIS activity.

Here is how he described the journey to me in his own words (without edits or corrections) followed by a cartoon he drew of Putin, Erdogan, and Assad squaring off on the Syrian/Turkish border:

The Way to Germany was not easy, becaus the Turkish goverment was paying a siege on syria, fearing of Terrorism. People have to hit by bullets sometimes.

I traveled in the rubber boat to Greece with a group of Syrians, every one had to pay 500 $

Them the way in europe was open to everyone, I traveled on board a liner to Athens, all the way you have to haggle with brokers and Mafias, transporting people by paying hundreds of dollers in each country.

There was a group of smugglers who deal with human smuggling.

I went to Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary to Austria then to germany.

By taking some of rented cars.

The risk factors were dealing with the Mafia. Also a lot of Thieves who were exposed to people on roads and in the woods.

As you konw, the Difficult is because the seriousness of the Situation, where you risk your life to get rid of the deadly dictatr Assad.

Med Malandi is one of the lucky ones who have asylum status in Germany. As such he is permitted to work though he doesn’t have the rights of a German citizen. He’s also been able to sell some political cartoons. Others are less fortunate. According to DW (Deutsche Welle), Germany’s international news organization, more than 890,000 migrants found their way to Germany during the 2015 crisis. Of those, 286,000, by far the largest number, were Syrian. In 2016 immigration slowed (280,000) but continues to put pressure on government resources. To date, 62% of the asylum applicants, like Med, have been approved, but there has been a recent backlash to Chancellor Merkel’s decision to admit so many migrants.

Just as there is a vocal minority in America who want to deport undocumented workers, there is growing anti-immigration sentiment in Germany. As a result, the ultra-right wing Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) party captured 13% of the vote in the September election and Merkel, without a large majority, is finding it hard to build a governing coalition. For the first time since World War II a neo-Nazi party is establishing itself as a viable political choice.

The United Nations High Commission on Refugees reports that 65.6 million people are currently displaced from their homes worldwide. 22.5 million of these are refugees (over half of whom are under 18). 10 million are stateless. According to UNCHR figures only 189,000 refugees were resettled in 2016.

It’s important to draw a distinction between refugees and migrants. Refugees, as defined under the 1951 Refugee Convention, are entitled to basic rights under international law, including the right not to be immediately deported and sent back into harm’s way. “The practice of granting asylum to people fleeing persecution in foreign lands is one of the earliest hallmarks of civilization,” according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. “References to it have been found in texts written 3,500 years ago, during the blossoming of the great early empires in the Middle East such as the Hittites, Babylonians, Assyrians and ancient Egyptians.”

A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her home country because of armed conflict or persecution. Syrians are prime examples.

The U.N.’s definition of refugee is someone who, “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

All refugees are migrants, but not all migrants are refugees. People leave their homes for many reasons, most commonly to seek a better life in a place with more opportunity, but these migrants have no protected status unless they are refugees. Migrants are processed under the receiving country’s immigration laws and policies and though migrants may seek to escape harsh conditions in their home countries, refugees might face imprisonment, deprivation of basic rights, physical injury or worse.

Med Malandi haunts me. I know he’s safe now, but there are millions, literally millions, of people like Med who are not safe, people without a home or country to call their own. It calls for compassion, something that seems in short supply in our chaotic world. I ask you to be your best self and lend a hand if you can. As the Christmas season approaches a donation to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) might be your way to contribute toward a compassionate solution to the refugee problem. It’s more pressing than climate change or Russian interference and will be for the next decade.