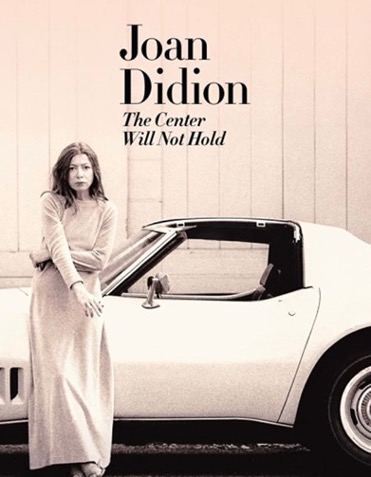

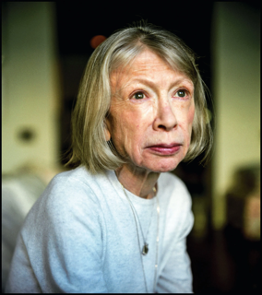

She’s been leaving us since 2003. She invited us to watch, and today she took her final breath. Joan Didion was the consummate detached observer. In the beginning, her strength was cultural commentary, reporting on-site in the Haight-Ashbury during the 1960s flower power/LSD days (Slouching Toward Bethlehem). Then we were allowed to ride along while Maria Wyeth aimlessly roamed LA’s freeways and mentally unraveled in Play It as It Lays. But her writing didn’t become painfully personal until the sudden death of her husband and writing partner John Gregory Dunne and the subsequent death of her daughter Quintana Roo. It was as if she couldn’t help scratching the open wounds of loss (The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights). Since then, we’ve morbidly watched as Parkinson’s Disease shriveled her body and flattened her once animated face.

I will miss her keen, acerbic observations and spare prose, but most of all I will miss her cultural commentary. For a writer whose work is packed with insights into political intrigue, she was curiously silent on Trump and the ramifications of his political legacy. In Political Fictions she commented on the Clinton years, and how a “handful of insiders (who) invent, year in and year out, the narrative of public life”. And, in Salvador she wrote of her terrifying awareness that death squads were stalking the country while she wandered the aisles of a shopping center that offered imported vodkas and foie gras.

As the year-ends, I’m acutely aware that Ms. Didion’s death marks another kind of passage. Her voice won’t be around to remind us of the importance of family, the pain of personal loss, or the global consequences of ignoring political terror.

The past two years have been a trial. Americans have seen 800,000 fellow citizens die of a rampant uncontrolled virus, were forced to confront their country’s history of racism, watch an attack by domestic terrorists on its nation’s Capital, see the outgoing president attempt to overturn a legitimate election, and suffer the humiliating withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan after a 20 year war it couldn’t win.

Life changes fast.

Life changes in the instant

You sit down to dinner and the life as you know ends.

The question of self-pity

Joan Didion (The Year of Magical Thinking)

It seems appropriate to give her the last word.