We may all have a case of cabin fever but there is no scarcity of good books, videos, films, and music to keep us occupied while we wait for Covid-19 to be vanquished. On Sunday night M and I watched a beautifully made PBS documentary American Masters:Wyeth, chronicling the life and work of Andrew Wyeth the great American realist painter–who lived most of his life, by choice, in self-isolation.

While taking an art history class in the 1950s, I became aware of Mr. Wyeth’s work but didn’t understand how to place it in the continuum of American art. Neither did the arts experts; realistic painting seemed old fashioned to them. But, in 1948, Alfred Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, purchased what has become Wyeth’s most famous painting, Christina’s World, for $1800 and that act helped change the art world’s perception of what “might” be modern. At the time abstract expressionism (Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clifford Still and others) was the big thing in modern art and realism was out of favor and assigned to a place in art history.

In 1968, my former wife, Abby, and I were invited to visit our friends, Harry and Diana, in New York and travel to Maine with them where his family had a summer home at Owl’s Head. This lobster fishing village had become a summer refuge for a few old New York and Boston families, and on our arrival Harry’s mother, who knew Abby was a painter, suggested in her sly way that he take us down to the General Store. It seemed odd but we were their guests and went along to see what was up. It was an old-fashioned country store that sold food, clothing, nails, and kerosene but that wasn’t the point. The proprietor knew Harry and when asked if he would take us into the family living area he agreed. We were astonished when we entered and saw three Andrew Wyeth paintings on the rough lumber walls of the family’s living room.

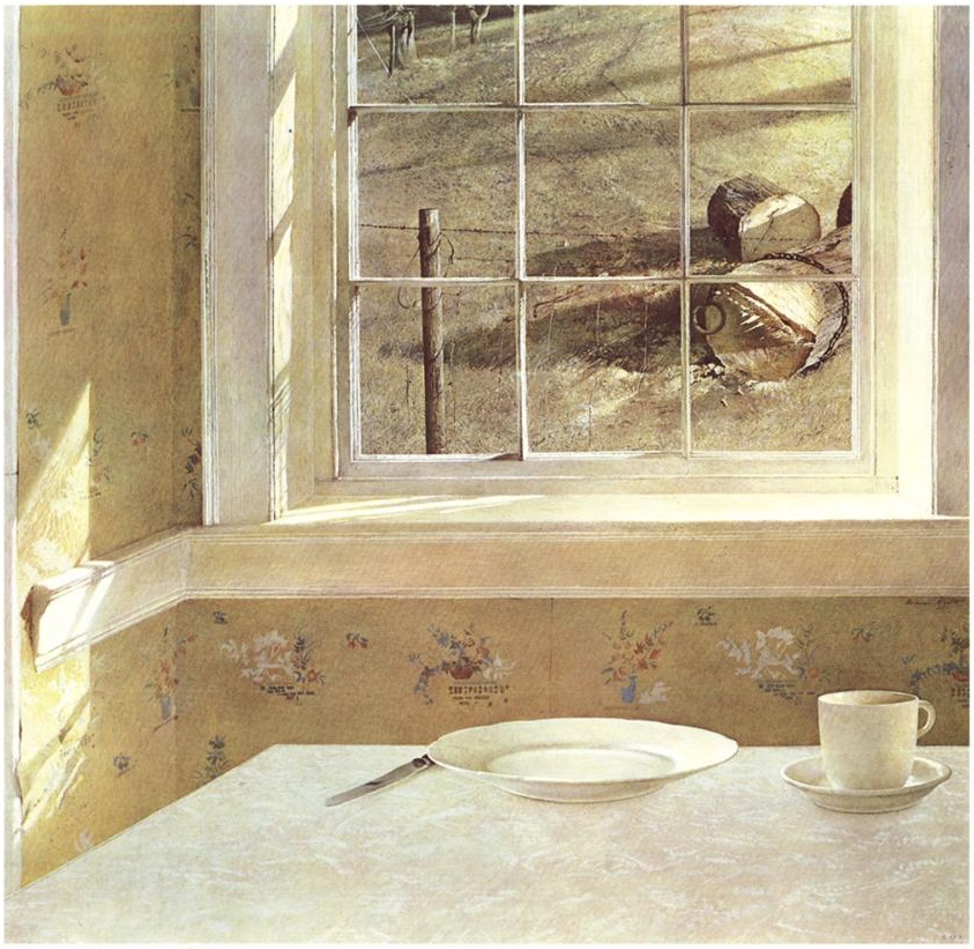

I couldn’t identify the paintings now. I like to think the painting of this window with curtains blowing in was one of them, because it reminds me of the living room in the old country store. It probably was not, but I love the story and how the proprietor came to own them.

Wyeth, wife Betsy and their children spent their summers in another town, Cushing, not far from Owl’s Head, and Wyeth, then a poor artist, traded the paintings for food and supplies. I’ve added the story to my collection of six-degrees of separation experiences, and it has enhanced my interest and appreciation for this remarkable artist.

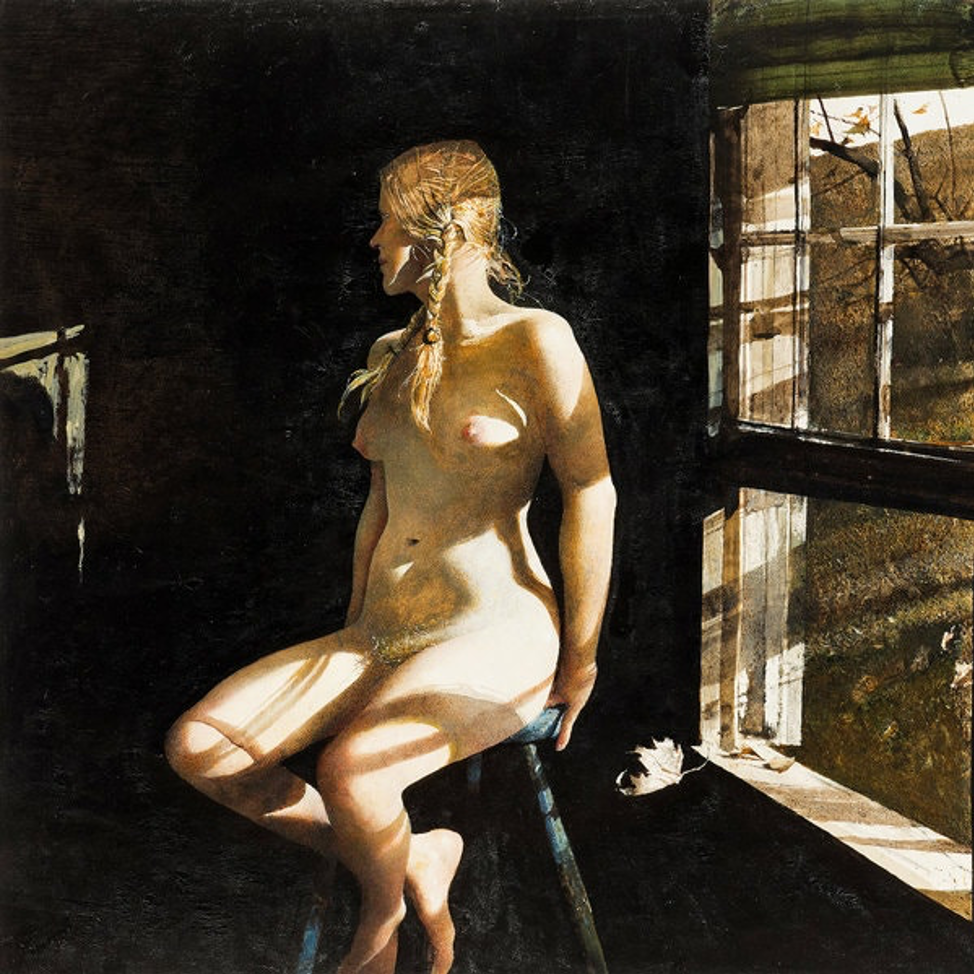

Wyeth, who died in 2009, was celebrated in 2017 with an expansive retrospective at the Seattle Art Museum on the 100th anniversary of his birth. It was a blockbuster show that included work from all periods of his career, including landscapes of the area around Chadds Ford, portraits of his German neighbors the Kuerners, sketches and paintings of black families who migrated to Chadds Ford following the Civil War, and the scandalous “Helga paintings” (more than 240 paintings of a neighbor done between 1971 and 1985) a secret he kept even from his wife, Betsy.

One more six-degrees of separation experience also involves my friend Harry. Following his divorce from Diana, he had a brief affair with a woman who was a White House intern during the Kennedy administration. There, her co-worker was Phyllis Mills who later became Jamie Wyeth’s wife. She, Phyllis, was crippled in a car accident in late 1962 and when Harry and his girlfriend went to Chadds Ford to visit Phyllis she took them around in a horse drawn carriage – her preferred means of travel.

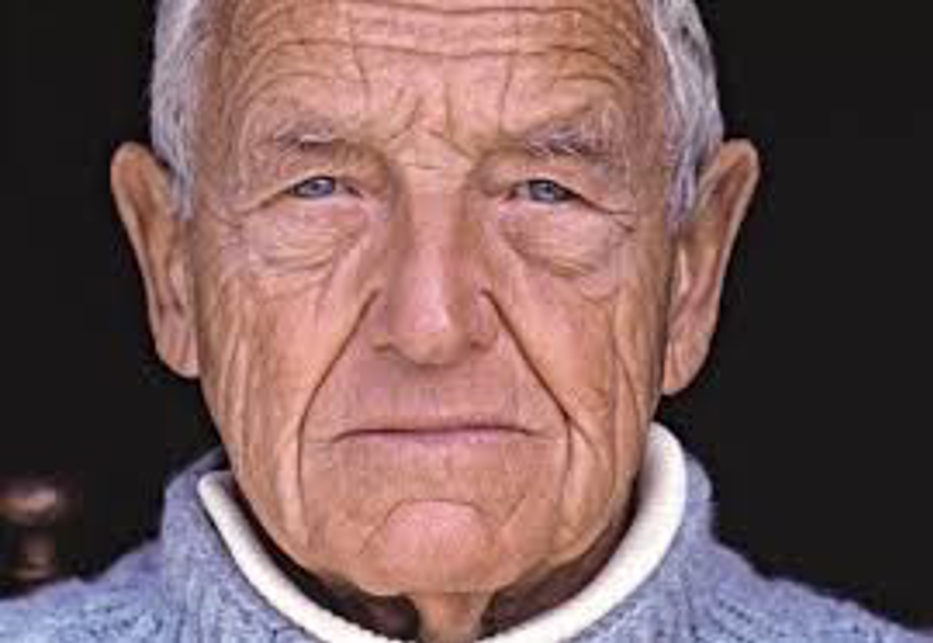

American Masters:Wyeth gives us a comprehensive look at one of America’s best known and most unique art families. Andrew was the son of N.C. Wyeth the famous illustrator of Treasure Island and other Scribner Classics and father of Jamie, famous in his own right for carrying on the realist tradition of his father. All the Wyeth painters, father, son, and grandson were without formal art training, schooled only by their fathers who rarely left Chadds Ford and who took their subject matter from the local surroundings. Three generations living in virtual isolation at Chadds Ford PA and Cushing ME is evidence that a rich life can be lived without the stimulation of the big city, world travel, and fine dining. Look around. Andrew did and from the people he knew and ordinary surroundings he lived in he created a rich and revealing world.

What a face!