Ever since that theatrical moment when he and Melania – rode the escalator from their gilded palace in Trump Tower to the food court below – I’ve been trying to find a suitable metaphor, real or literary, to describe the unfolding drama of our times.

Before the inauguration I thought Donald Trump might be our Great Gatsby, and I even wrote an essay making the equation. http://www.jackbernardstravels.com/djt-great-gatsby. Like Jay Gatsby, Trump is a larger than life character removed from the concerns of ordinary people. Both characters cultivate images as self-made empire builders with self-inflated biographies. Both crave acceptance by the elite they will never be a part of and surround themselves with leeches and hangers-on. Both love extravagant trappings and beautiful women, and Trump would no doubt be flattered by the comparison. Even if he doesn’t read or know the story, to see himself as a character portrayed by Robert Redford or Leonardo DiCaprio would stroke his unquenchable ego and delusional image as a handsome leading man of unimaginable wealth.

But differences abound; Gatsby’s Long Island estate is an “old money” property not a midtown Manhattan tower built by Mafia thugs using cheap materials. No, Trump is definitely not Gatsby. Both are imposters, and neither is what he seems, but Gatsby has good taste in trappings and women. He isn’t a nouveau riche vulgarian from Queens who chases models and thinks gold toilets are symbols of class.

Gatsby, like Trump, is a criminal. He made his money as a rum runner and does business with criminals but is brought down by a case of mistaken identity. It could happen to Donald as well. Wouldn’t it be ironic if a porn star, a Playboy model, and some Russian hookers are the ones that drive the final stake in Donald’s mythology? Just desserts in a fake world. Fake gold. Fake tits. Fake hair. Fake tan. No, Donald Trump is not our Great Gatsby.

But, who is a comparable figure? Is it John Gotti, the Teflon Don (no pun intended). He comes to mind, but he’s too smooth, too well dressed and too well-spoken. Like the Donald, he’s a ruthless criminal surrounded by henchmen and it’s entirely possible the Donald will also end up behind bars. How about Tony Soprano? Is he too real? Too earthy? Too invested in his team? Donald would sell his children if it would save his skin (or hair). Or, how about Bernie Madoff? He fooled a lot of smart people for a very long time…and while the Donald may have fooled his base, he never really fooled us. We always knew he was a fraud. Those of us who have observed him over the years have always known he was a liar, a fake, and thin-skinned trickster.

So, if it’s not Gatsby or Tony Soprano, is there a better analog? Lately, I think the better metaphor is Lear, the king who loses his grip on reality and family. Surrounded by a “mocking Fool,” greedy family, and sycophants who flatter him ceaselessly, we watch as he gradually descends into madness ranting that the whole world is corrupt. Unable to trust those around him, he yields to his impotent rage. No comparison is exact but this one seems apt. I have a hard time thinking of Trump as a Shakespearean character except as a comedic Falstaffian foil (a fat, vain, boastful, cowardly slob who surrounds himself with petty thieves). But, Shakespeare keeps surprising us with how contemporary he is, and staging King Lear today he might choose Trump as the tragic king who gradually descends into madness while his family dissembles and the kingdom suffers.

Since last week’s midterm elections, he has taken on Lear-like characteristics. He sees himself under siege. The press is after is ass. House Democrats are emboldened and threaten like wild dogs. The Mueller investigation haunts him. His former confidants Cohen, Manafort, Rick Gates, Flynn, and Roger Stone are all under indictment or soon will be. He rages about an immigrant invasion coming from the south. He’s paranoid about leaks and doesn’t trust anyone but family and Sean Hannity. His wife orders the firing of a deputy national security advisor and he complies. He fires Jeff Sessions and appoints an interim AG whose last job involved selling fraudulent time travel, Sasquatch verification, and toilets. He exiles staffers, promulgates conspiracy theories, photoshops videotapes of a White House press conference, withholds press credentials, and lashes out at African-American women reporters. He rants about rigged elections, voter fraud, and patriotism, but he can’t drag his sorry ass to a WWI cemetery in France or Arlington National to honor the dead on Veterans Day.

Rain… Bad hair day… Enemies everywhere.

And, Ivanka… perhaps his last true ally, like Lear’s daughter, Cordelia, has made herself scarce amidst the shitstorm. Even his few remaining allies are terrified. WTF are we Americans to think of an ignorant lunatic formulating foreign policy based on what Fox and Friends reports in the morning or Sean Hannity tells him at night. With the power and resources of the entire US government at his disposal he takes his cues from Hannity, and Alex Jones.

God save us.

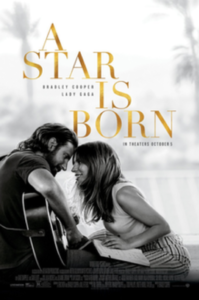

As a movie fan I’m often surprised to learn how long it takes to bring a film project to the screen. What seems like an of-the-moment performance may take years to find its way to a theater near you. That’s certainly true of the newest version of A Star is Born starring Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga. Like its earlier versions, this is the story of an older star who discovers a young talent, falls in love with her, but is ultimately destroyed by alcohol and jealousy as his protege’s star brightens while his own grows dimmer.

As a movie fan I’m often surprised to learn how long it takes to bring a film project to the screen. What seems like an of-the-moment performance may take years to find its way to a theater near you. That’s certainly true of the newest version of A Star is Born starring Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga. Like its earlier versions, this is the story of an older star who discovers a young talent, falls in love with her, but is ultimately destroyed by alcohol and jealousy as his protege’s star brightens while his own grows dimmer.

On Saturday, a deranged, un-closeted bigot murdered 11 elderly Jewish congregants and injured 6, including 4 police officers who were attempting to halt the slaughter at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. Earlier in the week, in another part of the country, the FBI was working diligently to uncover the identity of an unhinged bomb-building Trump zealot who mailed 14 pipe-bombs to two former presidents and twelve other Trump critics.

On Saturday, a deranged, un-closeted bigot murdered 11 elderly Jewish congregants and injured 6, including 4 police officers who were attempting to halt the slaughter at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. Earlier in the week, in another part of the country, the FBI was working diligently to uncover the identity of an unhinged bomb-building Trump zealot who mailed 14 pipe-bombs to two former presidents and twelve other Trump critics.

In Israel, the hard right-turn of the government, and its aggressive, unauthorized building of settlements on the West Bank, combined with the Trump administration’s provocative Embassy move to Jerusalem and withdrawal of financial aid to the UN Palestinian Refugee Fund and Gaza to put an end to talk of a two-state solution. It’s difficult to imagine two self-dealing heads of state like Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump, both under investigation for corruption by their own governments, making any effort to help the Arab and Palestinian populations take a meaningful step toward statehood. And, with a rank amateur like Jared Kushner in charge of Middle East policy it’s a setup for even greater tragic error.

In Israel, the hard right-turn of the government, and its aggressive, unauthorized building of settlements on the West Bank, combined with the Trump administration’s provocative Embassy move to Jerusalem and withdrawal of financial aid to the UN Palestinian Refugee Fund and Gaza to put an end to talk of a two-state solution. It’s difficult to imagine two self-dealing heads of state like Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump, both under investigation for corruption by their own governments, making any effort to help the Arab and Palestinian populations take a meaningful step toward statehood. And, with a rank amateur like Jared Kushner in charge of Middle East policy it’s a setup for even greater tragic error.