In 1517, this cranky professor of moral theology was so upset by corruption within the reigning power structure that he risked everything to challenge it. Martin Luther’s complaint exposed the corrupt Papal practice of selling indulgences in exchange for the absolution of sins. When his complaint went uncorrected he nailed his objections (95 Theses) to the door of the Cathedral at Wittenberg, leading ultimately to the Protestant Reformation.

Oh please… Martin Luther, please come back. We need you.

We are in desperate need of a secular Luther to challenge the White House’s current sale of indulgences. This looks a lot like the Catholic hierarchy of the 16th Century where Popes and Cardinals accepted bribes, lived like kings, took advantage of the poor, and fathered numberless children while claiming the moral high ground.

We need a reformer who can actually drain the stench-ridden swamp in and around the White House. Is he out there – our American Martin Luther? Right now, I hear a Babel-like chorus of unhappy Americans but no obvious leadership pulling them together.

One year into the Trump’s death spiral, he and his cabinet (above) have already done serious harm to America, its citizens, and its alliances. Internationally, he has withdrawn from the Paris Climate Accords, a coalition of 119 nations working collaboratively to reverse the effects of global warming. Further, in the face of unanimous international opposition, he is backing Israel’s claim to Jerusalem as the rightful capital of Israel and planning to relocate the US Embassy while instituting a thinly veiled racist travel ban prohibiting immigration from seven predominantly Muslim countries.

Back at home, his administration has hardened its stand on undocumented immigrants, encouraging ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) to aggressively round up and deport “illegals” while phasing out DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), the Obama-era law that protected undocumented children who entered the country as minors.

Back at home, his administration has hardened its stand on undocumented immigrants, encouraging ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) to aggressively round up and deport “illegals” while phasing out DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), the Obama-era law that protected undocumented children who entered the country as minors.

On other fronts, he’s reversed a law barring mentally ill people from purchasing guns and another obligating financial advisors to put the interest of clients ahead of their own. Environmentally, he is targeting National Parks and monuments by taking steps to downsize and open them up to resource extraction while more than doubling the cost of entry fees.

It’s difficult to explain why these changes are occurring. He, unlike Obama, inherited a sound economy with near full employment. What, other than personal animus and greed, would motivate him to put a woman who never attended a public school in charge of public education or a man who denies climate change in charge of the Environmental Protection Agency. What is the rationale for appointing a man who made billions foreclosing on distressed homeowners (left) to be Secretary of the Treasury or a neurologist with no experience in housing or managing people to be Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Did he think a self-dealing doctor who didn’t believe in health insurance was the best choice for Secretary of Health and Human Services or the co-chairman of a Cypriot bank known for money laundering to serve as Secretary of Commerce. These appointments are unconscionable.

Drip, drip, drip… We have watched four of Trump’s campaign aides, including his campaign chairman and the former National Security Advisor, come under criminal indictment. The Office of the Special Counsel is closing in on Trump’s connection to the Russians and their attempts to undermine America’s democratic institutions. Americans need to update and modernize Luther’s 95 Theses to deal with this collection of bottom feeding swamp creatures. The sale of indulgences is ongoing, but Congress is silently holding its nose trying to pass a hopelessly flawed tax bill and avoid a government shutdown by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, Trump and his family continue to enrich themselves in a vast criminal enterprise that includes money laundered from drugs, arms, and human trafficking operations in Russia, the “Stans,” Central and South America, Turkey, and even New York. Much of the considerable debt incurred by the Trump/Kushner posse is money that passed through Germany’s Deutsche Bank, a bank that recently paid a $630 million dollar fine for laundering as much as $10 billion for unidentified Russian “customers.” In addition, a recent investigative report by Richard Engel of NBC documented the abuses and details of a money laundering pass-through at Trump’s Ocean Club Hotel and Tower in Panama City, Panama. The building is virtually uninhabited but most of its condo units were sold to mysteriously named, almost untraceable, shell-companies fueled with money from organized crime – much of it Russian – and the Trumps got a piece of every sale.

The dominos are falling on both sides. Claims of fake news emanate from the White House on a daily basis as journalists follow the facts and pursue the truth in what has become a golden age of investigative journalism. At the same time, the Department of Justice is monitoring Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s team as it digs into the relationship between Trump and the Russians in the 2016 presidential campaign. The dominos are falling inexorably toward a reckoning on Trump’s Russian gambit, but while that is slowly unfolding American institutions are being dismantled from within.

Special interests have taken advantage of the moral vacuum. Two-thirds of Americans think the President is on the wrong track but Congress remains silent. The State Department has been gutted. Environmental regulations have been rolled back. Health care is on the chopping block. The Acting Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) wants to shut it down, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) lapsed in September leaving millions of poor children uninsured.

As punishment for my last non-heroic feat as a Marine Corps fighter pilot, I received a 40 page Letter of Reprimand. My crime was flying too close to the ground – down 17th Street in Santa Ana “at car top level” according to the Santa Ana Register. That official letter of reprimand cited my “reckless and willful disregard for government property and the public’s health and safety.” I deserved the letter on top of being grounded for one year.

That language, “reckless and willful disregard for government property and the public’s health and safety” resonates with me as I observe the Trump administration’s dismantling institutions that are the foundation of our democracy – its free press, its separate judicial branch, its independent legislative branch, its equal protection of the laws, its due process, and its principle of “one man, one vote.”

Trump and his minions deserve a great deal more than a Letter of Reprimand, and I think they will get it. Their punishment may be judicial or electoral but it will come. Remember this language – “reckless and willful disregard”. Martin Luther might have used the same language in describing the corrupt self-serving actions of the Papal aristocracy. We’re still looking for our Martin Luther, but I have faith that he or she will emerge. Keep the faith.

Semper Fidelis

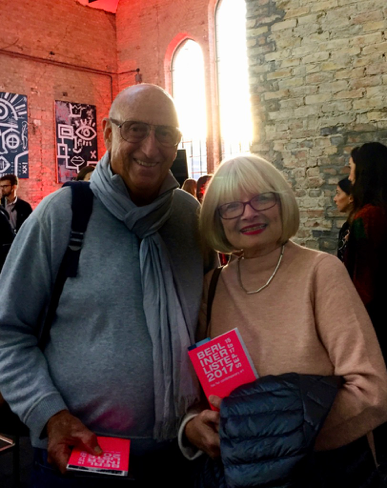

Roberto is an old soul who listened patiently as M related the story of the heist, the upset, the uncertainty – the whole catastrophe, chapter and verse. How she hates the bus. How we had bussed back to town from Andratx. How crowded it was. How tired and anxious we were to get back to our apartment. How we almost got on the bus. How we tried to chase the thief, took a taxi home, and Skyped America on Sunday night to cancel the credit cards.

Roberto is an old soul who listened patiently as M related the story of the heist, the upset, the uncertainty – the whole catastrophe, chapter and verse. How she hates the bus. How we had bussed back to town from Andratx. How crowded it was. How tired and anxious we were to get back to our apartment. How we almost got on the bus. How we tried to chase the thief, took a taxi home, and Skyped America on Sunday night to cancel the credit cards. After saying goodbye to Roberto, we walked up Sant Magi to our other favorite place, Bar Ventuno, a small corner bar-restaurant with a tall two-top outside near the front door. Ventuno only serves drinks and individual four piece pizzettas. It’s our late night “don’t-want-dinner-but-want-wine-and-a-bite-to-eat” place. The owner, Yari, whose mother and brother run La Casa Mia, a real Italian restaurant, just across the street is a hard working charmer. Yari and his waitress, Martina, have adopted us and waved to us for a month as we walked down the street even if we’re not going to their place.

After saying goodbye to Roberto, we walked up Sant Magi to our other favorite place, Bar Ventuno, a small corner bar-restaurant with a tall two-top outside near the front door. Ventuno only serves drinks and individual four piece pizzettas. It’s our late night “don’t-want-dinner-but-want-wine-and-a-bite-to-eat” place. The owner, Yari, whose mother and brother run La Casa Mia, a real Italian restaurant, just across the street is a hard working charmer. Yari and his waitress, Martina, have adopted us and waved to us for a month as we walked down the street even if we’re not going to their place. We’re so lucky. We’ve made friends everywhere we’ve gone. They seem to like us and we them. This is the true meaning of hands across the border. Crossing borders – cultural, linguistic, geographic, even culinary – to find common interests and values.

We’re so lucky. We’ve made friends everywhere we’ve gone. They seem to like us and we them. This is the true meaning of hands across the border. Crossing borders – cultural, linguistic, geographic, even culinary – to find common interests and values.