This is the main intersection in the small town of Glen Ellen, California. The street sign in the photo directs visitors to 23 local wineries and tasting rooms. Just over the hill from Napa and a few miles north of Sonoma, this is California wine country without the hype. You’re not likely to see any Ferraris here, no Guccied-up juice bars, no designer boutiques, or four-figure dinners for two. It’s the kind of place you might have run into M.F.K. Fisher or Hunter Thompson (both former residents) at the local supermarket.

Glen Ellen is one of those towns that surprises. It’s fun to discover such a place. It lies off the beaten track, 36 miles of winding road east of Petaluma. But, it’s not a new find. Charles Stuart found and purchased the land, which was part of an original California land grant, in 1859. He planted a vineyard and named it Glen Ellen after his wife. Nice story.

In the early 20th Century, before construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, the cooler, oak covered, rolling hills of Marin, Sonoma, and Napa counties gave wealthy San Francisco families respite from the summer heat.

Jack London discovered Glen Ellen in 1905, purchased 1000 acres, moved there with his wife, Charmian, to started construction on their dream home. Wolf House was to be a 15,000 sq ft wood and stone structure but it burned to the ground in 1910, two weeks before they planned to move in. Undaunted, they moved into a small cottage with adjoining writing studio where they lived until his death in 1916. After his death, Charmian built a smaller version of Wolf House on the property and called it the House of Happy Walls. She lived there until her death in 1955, when, per her request, the house became a museum to honor his legacy. In 1959 the entire property was designated a Historic National Landmark and protected as Jack London State Park.

Today, Glen Ellen has a population of 784, one hotel, three small restaurants, a car repair shop, and supermarket. This is wine country and there are upscale restaurants and country inns in the vicinity, but the town of Glen Ellen is a sleepy, residential community.

Marilynn and I had dinner at the Fig Café, a small, unpretentious restaurant within walking distance of our reasonably priced Jack London Lodge accommodations. The town may be sleepy, but the waitress at the Fig Café was as experienced and knowledgeable as she was friendly. When we asked about two rosés on the wine list, she differentiated between them and their provenance – Mathis, is a pale bone-dry European-style varietal made from Grenache grapes while Balletto, is a less flinty new world version made from Pinot Noir vines. We tried both with our fig and prosciutto flatbread appetizer and found them delicious.

The following morning after a visit to Jack London State Park and the museum, we continued east on California Highway 121 to Yountville, the heart of the heart of California wine country where we had trouble finding street parking between the Mercedes convertibles and Porsche Cayennes. When we did, we pulled our bikes off the car and crossed a busy Highway 29 to the newly made Rails to Trails bike path. The trail will eventually run from Napa all the way to Calistoga – from one end of the Napa Valley to the other – but at present only 7.5 miles have been completed. Though it lacks scenic appeal – it runs along the highway and side by side with the Wine Train railroad tracks – it does provide a car-free, stress-free alternative for moving through the valley.

The Napa Valley is justly famous for its wine (and food), so before moving on we stopped for lunch at Tra Vigne Pizzeria in St. Helena. I loved the original Tra Vigne, just down the street from the Pizzeria, but on our way in I noticed the original was no longer in operation. When I asked our server about it, she told us that the restaurant’s owners were unable to renegotiate their lease because the building owners wanted to replace it with an even more upscale restaurant. Michael Chiarello’s original Tra Vigne was not a cheap eats place, so I wonder what they have in mind? Michael moved on to other projects years ago though he returned to the valley recently to open Bottega Ristorante in Yountville.

Nevertheless, the fate of Tra Vigne speaks to the destiny of the Napa Valley itself. Wine has replaced horses as the Sport of Kings and Napa is Churchill Downs. The Mondavi’s, Beringers, and Trefethens are still there and continue to prosper from America’s wine infatuation, but many of the newer wineries are the rich kid pastimes of Wall Street executives and Silicon Valley venture capitalists.

Glen Ellen is a fresh breath of old wine country air. Yountville and St. Helena are showy places to see and be seen, but give me the rolling, live-oak covered hills of northern Sonoma County. Put me in a convertible on the winding eucalyptus-lined roads that lead in and out of Glen Ellen and you can have everything east of it. This is California wine country without the hype. This is my kind of place.

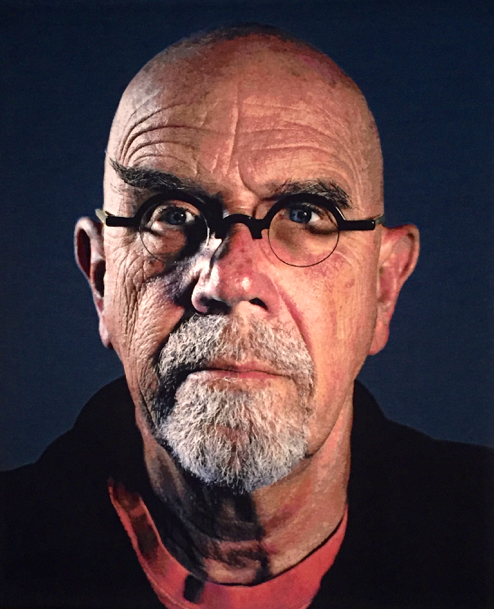

It was a raucous period in America. Good and bad. It was a time of experimentation and increasing freedom. The Pill was liberating both sexes from the fear of pregnancy. Timothy Leary and the Summer of Love were happening across the Bay in San Francisco. Bob Dylan, The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, and Santana were kicking it. Vietnam was heating up and in November of 1963 President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Last week Marilynn took this picture of me on the landing at Boalt Hall where I first heard the news of the horrific event that signaled the loss of innocence for our generation.

It was a raucous period in America. Good and bad. It was a time of experimentation and increasing freedom. The Pill was liberating both sexes from the fear of pregnancy. Timothy Leary and the Summer of Love were happening across the Bay in San Francisco. Bob Dylan, The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, and Santana were kicking it. Vietnam was heating up and in November of 1963 President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Last week Marilynn took this picture of me on the landing at Boalt Hall where I first heard the news of the horrific event that signaled the loss of innocence for our generation.