On September 30, 1965 I walked up the rear-boarding ramp of a C-130, grabbed a seat on a drop down bench, and within minutes we were wheels up on our way to Italy. I had leveraged my time as a Marine pilot to hitch a ride with a Navy Seal team on its way to NATO exercises in Italy. I had no plan, no itinerary, no return ticket, but it felt like the time was right for my first trip to Europe. The week before, I had taken the California Bar exam and the results wouldn’t be published until December. I was 26 years old and single. I had worked my way through law school and squirreled away enough money to travel for a few months. I was as free and unburdened as I would ever be. I was embracing the dictum of Harvard’s Let’s Go travel guide: “Travel light. Live close to the ground. See all you can. Stay until the money runs out.”

The C-130 landed near Verona the next morning, and for the next month I was on the move making new friends, sleeping on floors, riding trains, hitchhiking, seeing great art up close, and walking the length and width of every city I stopped at. From Verona I went to Milan, from Milan to Florence, and from Florence to Rome. In Rome I ran into a Greek-American classmate, named Pete, on his way to visit relatives in Athens.

“Hey, Jack, if you don’t have a plan why don’t you tag along to Greece. You’ll like it. “

I hadn’t thought about visiting Greece but my wanderlust kicked in, and the next day I was on my way to Athens.

After a train ride, boat ride, bus ride and taxi we arrived in the Greek capitol. Pete went off with his family and I was on my own again. My opinion of Athens has changed over the years, but on that first visit I found the noise and pollution paralyzing. The cars were all 1940’s vintage, because, like Cuba, taxes on imported vehicles were exorbitant so the old ones had to make do. The only thing that seemed to work were their horns so after a quick visit to the Acropolis I was ready to leave. I didn’t care where it was going, but I decided to take the first boat leaving Piraeus for an island. Any island would do. That night I was on my way to Crete.

The ferry was a tub, a big rusty tub, and traveling deck class meant I didn’t have a bunk or cabin. It was overnight passage at deck level inside a big bare room. There was a long table in the center where the men were seated. On the table were bottles of retsina, the resin-flavored Greek wine, hunks of cheese and various kinds of salami. The women, all in black, sat around the edges of the room. There were a couple of goats tethered to the ship’s hardware and passenger luggage consisted mostly of cardboard boxes held together with twine.

I found a chair in a corner and stashed my fold-over suitcase and guitar against the wall. The departure was after dark with an ETA at Heraklion sometime after sunrise. It looked like a long night on a hard wooden chair. I read for a while and then got out my guitar to help pass the time.

Soon, a small wiry man with a deeply creased leathery face and blazing smile approached me. I felt uncharacteristically awkward. I knew he didn’t speak English but I asked anyway. He kept smiling but shook his head, no. We both shrugged. He pantomimed playing the guitar and pointed at me. It made me feel even more uncomfortable. I had no confidence in my own playing, but wondered if he was telling me he played. I handed him the instrument, and he sat down next to me. It was obvious the guitar wasn’t his instrument, but within minutes he was improvising a bouzouki tune. The bouzouki is the mandolin-like instrument featured characteristically in Greek dance music.

My new friend motioned me to come out to the center table with him, and I did. Someone poured retsina into a dirty glass and cut me a hunk of sausage. I looked around the room. I felt like I had been dropped into a scene from Zorba the Greek. No one at the table spoke English but they kept smiling and refilling my glass.

At the end of the table my new friend was fiddling with the guitar and starting to make real music with it. I’ve always admired musicians who can improvise. Soon, I noticed a couple of the men in animated conversation with the guitar/bouzouki player. They stood up. I didn’t know if it was the start of a fight or something else. The room got quiet and the men moved to an open area in front of the table. The guitar was now a bouzouki and its sound filled the room. The two men stood back to back and began to dance. Others joined in, stomped their feet and clapped.

The sun came up before we got to the port in Heraklion. I stood at the rail with a little hangover. None of us had slept at all. The men had danced and the women clapped time until just before sunrise. One of the men who had been at the table approached me at the ship’s rail with a piece of paper. He explained as best he could, in sign language, that the bouzouki player, Leftiri, owned a taverna in a village called Rethymnon on the north coast and wanted me to visit. His address was written on the paper. Two days later after checking out the Minoan ruins at Knossos and looking over the town of Heraklion I took a bus to Rethymnon.

The old town showed the wear of centuries – tilted whitewashed houses on narrow stone streets, an ancient fort on a hill, a picturesque small harbor where Leftiri’s taverna was located across the water from a breakwater wall and lighthouse. Though it started out as a side trip the town looked like the kind of place I might be able to slow down and catch up with myself. Within hours I decided to stay until it felt like time to go – a week or a month, maybe longer. I was unscripted.

What was it about Rethymnon that so captivated me? Was it the sight of three old men seated outside the taverna dragging on water pipes or the women dressed entirely in black scurrying through the narrow streets? Venetian traders established the town in the 13th Century when they built a fortress on the high ground to protect their secluded maritime harbor. Though the Ottoman Turks later conquered them the town remained relatively unchanged until recently.

As late as 1965 it relied for its sustenance on olive groves above the town and a small fishing fleet moored below. But it wasn’t the architecture or economy that gave this Greek village on a rocky barren coastline its appeal. It was its differences. Life on the island of Crete was so different from the one I knew. It was jarring and moved me to look more carefully at my own way of life and the advantages I had always taken for granted. It became clear that this solo journey was about more than landscapes, fortresses, or picturesque harbors. It was an internal journey as well.

For three years I had been in the law school pressure cooker, and for four years before that I was flying supersonic fighters on aircraft carriers. During those years I hadn’t stopped to ask myself basic questions about family, friendship, career, and other life goals. I had been living an adventure, but now I was in an unfamiliar setting only a short distance from the spot where Socrates proclaimed, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” It seemed fateful; the village, and it was a village then, was offering itself to me as a setting where I could examine my life and thoughtfully consider my future.

Others might see it differently, but I saw my process as aided by my foreignness. Because we spoke only smatterings of each other’s languages I couldn’t have deep conversations with my new friends, but we were able to communicate in other ways and our mutual like for each other transcended the language barrier. I’m friendly but not gregarious, and once the townspeople determined I was not German – the people of Crete have never gotten over the German occupation of their island in WWII – they accepted me as their American friend and left me alone. They smiled, nodded, and greeted me with “Kalimera” or “Kalispera” (good morning/good evening) depending on the time of day and I responded with “Efharisto” (thank you) or Parakalo (your welcome) as appropriate.

My “hotel” in the center of town had four small rooms. My room had a bed, sink and a bathroom down the hall. In addition to Lefteri, the bouzouki player, I made two other friends; Costas, a stocky local businessman who served as the town’s tourist connection and Marko, the slight, balding, town librarian who fought alongside the Americans in Korea and once spent five days in “San Fronseesko.” Marko managed a small library with a shelf full of English books donated by USIA. It was a quiet place I visited daily to read, write and think without distraction. Life in Rethymnon was simple.

When I asked about places to swim, Costas pointed to the west and waved his hand indicating there were many such places out that way. The next day I walked until I couldn’t see the town behind me and climbed down a cliff to the water. For the next six weeks I went there every day, lay on a flat rock a few feet above the clear green water, and baked until I couldn’t stand it any longer and had to dive in.

When I asked about places to swim, Costas pointed to the west and waved his hand indicating there were many such places out that way. The next day I walked until I couldn’t see the town behind me and climbed down a cliff to the water. For the next six weeks I went there every day, lay on a flat rock a few feet above the clear green water, and baked until I couldn’t stand it any longer and had to dive in.

My routine didn’t vary much over the six weeks I was there; coffee (Nescafe) at a small café in the morning, two or three hours reading and writing in the town library, sunning and swimming in the afternoon, dinner with Costas or Marko at one of the two restaurants in town, and every few nights ouzo and dancing at Lefteri’s taverna in the port. It was a unique experience and launched me as a lifetime traveler.

Six weeks after arriving on the island I rode the same bus back to Heraklion and boarded a small ferry to the island of Rhodes. Reading my journal from those days, it seems oddly out of time – or timeless. The writing is clumsy and inarticulate but the wonder and intensity of the experience are there. Rethymnon was like first love. It can’t be recreated but remains a vivid memory.

After a lifetime of travel I can say with some authority that the best travel experiences are usually the unplanned ones. They bring an element of surprise and discovery. They leave indelible memories. They encourage us to try new things. Some youthful adventures seem reckless or irresponsible in retrospect and maturity is likely to temper our urge to “go for it,” but flexibility and intuition are still key elements in allowing space for a transformational travel experience – at any age.

The urge to travel is in my DNA and that first solo trip to Europe allowed me to express it in a new way. I couldn’t be more grateful. Efharisto!!

NOTE: The town of Rethymnon is now a city. The boundaries are not clear but the population of the regional unit called Rethymnon ranged from somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 in 1965 to almost 50,000 in 2010. Large tourist hotels now dot the coastline where I swam alone. Tourism has replaced fishing and agriculture as the main source of revenue.

I’m happy for the people of Rethymnon. I’m sure life is easier now than it was then. Jobs are more plentiful and the town is more prosperous, but it saddens me a little to think about the changes. I know the old town remains much the same, but I feel privileged to have seen and experienced it when and as I did.

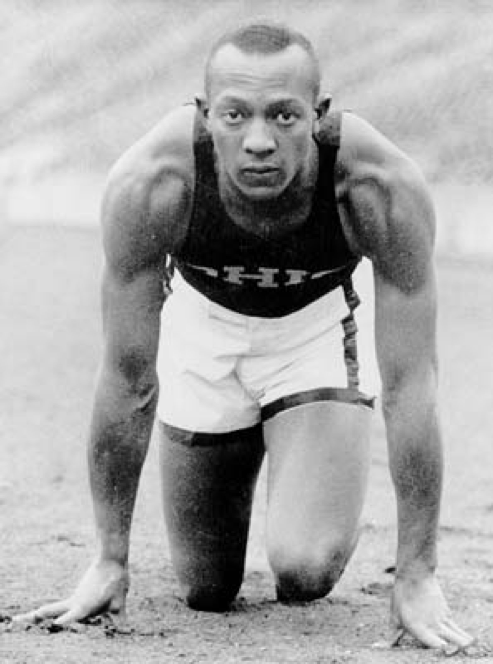

It’s sometimes difficult for us to accept America’s history of slavery and racism while we celebrate triumphs like Jesse Owens’ remarkable performance at the ’36 Games. Race does a credible job of showing the discrimination and indignities Owens suffered as he prepared for the Olympics and following his triumphant return to New York. In one touching scene he and his wife are prevented from entering the Plaza Hotel through the front door and directed to the service entrance in spite of the fact that the event they were attending was being held to honor him and celebrate his victories.

It’s sometimes difficult for us to accept America’s history of slavery and racism while we celebrate triumphs like Jesse Owens’ remarkable performance at the ’36 Games. Race does a credible job of showing the discrimination and indignities Owens suffered as he prepared for the Olympics and following his triumphant return to New York. In one touching scene he and his wife are prevented from entering the Plaza Hotel through the front door and directed to the service entrance in spite of the fact that the event they were attending was being held to honor him and celebrate his victories.