Starbucks and public libraries have become offices and workspaces for the free-wheeling, untethered GenTech demographic – students of all levels, flextime workers, freelancers and other self-employed. I never gave serious thought to a full-blown retirement, but three years ago when I left the world of the regular paycheck I started looking for a work environment where I could feel comfortable and productive as I started the next phase of my work life. In that process I tried various coffee shops, libraries, public spaces, and and my own home as offices but I disliked the choking air, obligation to buy, and smelly clothes that came with Starbucks, the library spaces that never felt comfortable or private enough, and the distractions of working at home.

Last week I tried a new “office” at Folio, Seattle’s start up non-profit whose avowed purpose is to serve as “a gathering place for books and the people who love them.” It sounds pretentious, but it’s actually a warm, welcoming, and uncrowded place. Among other benefits it offers members a lending library, reading room, workspace and a congenial staff – all for $125 a year. I wrote about it a couple of months ago when it was just an idea, but it officially opened on January 20th and I began using it last Friday. I’ve only tried it once, but Folio seems to meet all of my workspace needs.

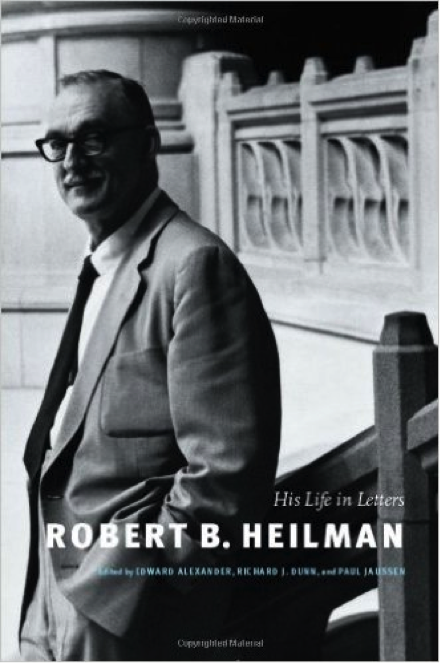

What could be better than a quiet space surrounded by books and comfortable places to read them? I’ve mentioned before how I love bookstores and can’t walk by a used or bargain book counter without seeing something that feeds my curiosity. At Folio, near the reception desk there are two tall bookcases; free books in one and $2 books in the other. Both are overstock from collections donated to Folio. Friday, I discovered the Robert Heilman book of letters (above) in the $2 bookcase and bought the 900-page volume without even looking inside the cover. Dr. Heilman was the Chairman of the English Department at the University of Washington from 1948 – 1975. I remember him with great respect; as the Chairman when I was an undergraduate and, coincidentally, as the father of my friend Pete Heilman.

The Heilmans were not close friends of my family, but one of my favorite personal stories from those college days occurred when Pete asked if I would like to have dinner at his parent’s home. They were planning to entertain Theodore Roethke, his wife Beatrice, and Roethke’s publisher at Rinehart. It was a big league invitation and heady company for a 19 year-old English major. I was nervous and excited at the same time.

The evening began with small talk in the Heilman’s kitchen, including a story of how Thomas Wolfe, a physical giant, who as he was writing You Can’t Go Home Again used the refrigerator in another Heilman home as his desk, and wrote on it standing up while keeping up his side of an ongoing conversation. My eyes and ears were popping. Famous literary names were dropping everywhere.

When dinner was ready we moved to the dining room. Pete and I hardly spoke. He was probably used to it, but I was awestruck. Roethke was already a Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning poet. Five years later James Dickey described him as “the finest poet now writing in English,” and added, “I say this with a certain fierceness knowing that I have to put him up against Eliot, Pound, Graves and a good many others of high rank.” Pete’s father, in turn, was a nationally recognized Shakespearean scholar, and his mother was an English teacher at St. Nicholas School. The publisher from Rinehart was an urbane New Yorker with a Yale pedigree, and I sincerely hoped none of them would ask me a question.

During dinner someone made a comment that provoked a lot of laughter, including mine. Everyone laughed except Roethke who quizically said, “I don’t understand the allusion.” I cringed. Roethke had a history of mental illness, had been in and out of several institutions, and though an excellent teacher was a little scary and unpredictable in class. I didn’t understand the allusion either but was embarrassed to admit it and feared that by his question my ignorance would be revealed. It wasn’t. In fact, nobody noticed me at all. Roethke’s confusion was quickly addressed and the whole exchange took less than a minute, but it got my attention and stuck with me. The smartest man in the room was not afraid to admit he didn’t understand something. It was a first hand lesson in honesty and humility.

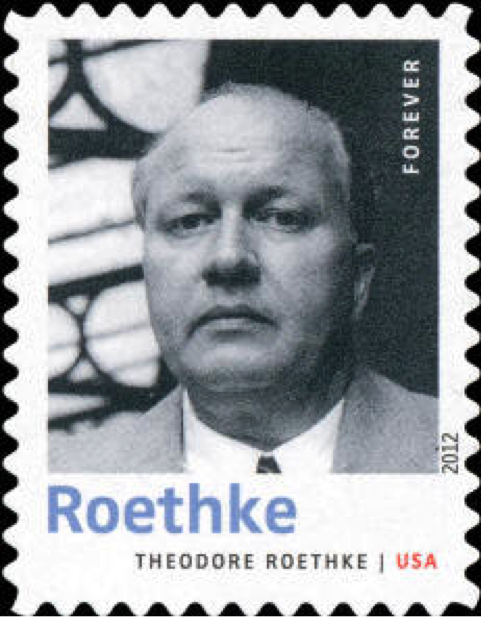

This is the US Postal stamp of Roethke in its poet series, and below it my favorite of his poems:

The Waking

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep but take my waking slow.

Of those so close beside me, which are you?

God bless the Ground! I shall walk slowly there,

And learn by going where I have to go.

Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?

The lowly worm climbs up a winding stair;

I wake to sleep but take my waking slow.

Great Nature has another thing to do

To you and me; so take the lively air,

And, lovely learn by going where to go.

The shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

The Heilman book is fascinating. Younger folks might not appreciate it and think it dated, but the correspondence includes serious discussions with many of the literary giants of the 20th Century – Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, Charles Johnson, Robert Penn Warren, Malcolm Cowley, William Carlos Williams, Roethke and many others. There are in depth letters that discuss the House Un-American Activities Committee’s threat to freedom of speech and the anti-Communist purges of the 1950’s as well as lighter ones in which Dr. Heilman complains to Robert Penn Warren about the chaos and mess his grandchildren create when they come to visit.

I don’t plan to read the Heilman letters cover to cover, but I do plan to keep the book on the coffee table for a while. It’s great reading in short spurts. Open it to almost any page and it reminds me that before email, Facebook and Twitter there was another form of written communication – serious, thoughtful, engaging, slowly written, thought provoking conversation on paper between two people with ideas to exchange.

This is a picture of Parrington Hall on the University of Washington campus where Dr. Heilman, Theodore Roethke, David Wagoner, Charles Johnson, Angelo Pelligrini and other’s shared their love of literature with those of us lucky enough to have them as teachers and mentors.