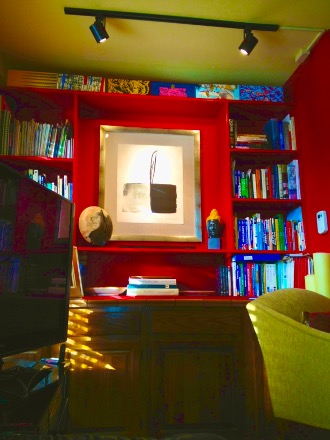

When M and I were working in Saigon, we lived in a tidy minimalist apartment. Three rooms, tile floors, built in appliances, TV console, small sectional, kitchen table, bed and writing table. It was uncluttered, and we loved it. So it was a shock to come back to Seattle, open the door to our condo and confront the overwhelming amount of stuff inside. Rugs on top of rugs. Walls full of books. Art on every surface. Closets full of shirts, suits, jackets, sweaters, shoes, linens, blankets, luggage. Two televisions. Two computers. Two desks. Two chests. Three sofas. Tables. Chairs. Filing cabinets. And a storage locker in the basement. Contrast raises your consciousness.

It’s probably stage-of-life related, but today we find ourselves whipsawed by the stuff of our lives–the decades worth of accumulation. Now, approaching our respective expiration dates, we’re aware of the accumulation and what it means. It’s part of the wrap up. Who gets what, or better yet, who wants what? It’s going somewhere, maybe family, maybe the Goodwill

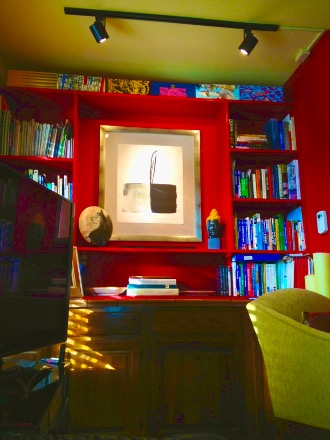

We’re not collectors or connoisseurs but we love the art, ceramics, books, rugs, and furniture we’ve collected. I could easily pitch the six fake Rolex’s I bought in Asia (though they all still keep time), but it will be hard to let go of the Toko Shinoda print I bought at Yoseido Gallery in Tokyo, the Persian rugs we bought from our friend, Ahmad, or the Raku platter I watched Jim Romberg “throw” in Sun Valley.

HBO’s recent release of a 2-part biopic on George Carlin brought it all back and triggered a tipping point in “stuff” awareness. Carlin first brought stuff to our attention in 1981 with an album called A Place for My Stuff, and though George and his stuff are gone (he died in 2007), his art lives on and so does his riff .

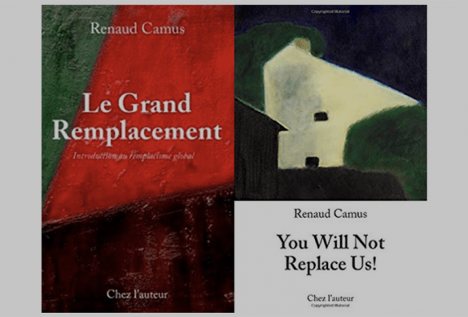

Carlin’s hilarious improvisation also reminds me that “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” How else to respond to the sudden appearance of NFT’s (non-fungible tokens), a one-of-a-kind digital asset. I can’t wrap my head around a digital picture worth $1,000,000. It’s not a painting or a photograph but it may be a picture of a painting or photograph. My trash. His treasure. It seems to me, NFTs are for people with too much money and not enough imagination.

But stuff is always loitering in our consciousness. Designers and efficiency experts keep reminding us to tidy up, clean house, or just get rid of the junk we’ve stashed in the basement, closet, under the bed, or in the attic.

I’m not talking about demented hoarders who can’t get rid of anything and need to create aisleways in their homes to get from room to room. That’s a sickness. I’m talking about ordinary people—about you and me–and our accumulated stuff. Nor am I talking about Marie Kondo who hit the scene in 2014 with her OCD tidiness blitz that had America tossing everything from family heirlooms to second frying pans so they could live minimally. For her and her followers, it was all about “decluttering.”

Hoarders and Marie Kondo aside, others have also weighed in. The writer, Ann Patchett, joined the parade in 2017 with an essay called My Year of No Shopping (included in her recent essay collection – These Precious Days). She recalls how a friend inspired her to go through her house to rid herself of the things she didn’t use, want, or need but had accumulated over the years – dishes, mismatched goblets, dolls from her childhood, broken pottery, etc. – cart them down to the basement and ask friends to come over to see if they wanted anything before taking them to the thrift store. It’s a good essay and a plan of action that might work for all of us.

It’s a given that stuff can trigger a passionate attachment. I’m that way about a few possessions, but nothing of great value. On the other hand, I have friends with collections full-size merry-go-round horses, silver inlay snuff bottles, soft-paste porcelain, and Madame Alexander dolls, collections of great value but whose children have no interest in inheriting them. They’ll undoubtedly be sold at auction, but the parents will be disappointed that their years of collecting stir no feelings of attachment in their children.

Our relationship and feelings about things change – obviously – over time. In my own case, when my former wife and I were first married and living a hippie life in Mill Valley, she inherited a set of Baccarat crystal stemware – wine, water, and sherry glasses – from a great aunt. Mary Alice’s crystal was etched with a flower pattern, so fine, so thin, and so beautiful it took your breath away. They belonged in an elegant brownstone, but we lived in a one room “apartment” under a crooked old Mill Valley house with a mattress on the floor, two beanbag chairs, and a hollow core door made into a desk/dining table. The Baccarat was museum quality, but we weren’t. Slowly, over a year the glasses cracked and shattered. First the sherry. Then the wine. Then the water – because they were the least used. It was almost criminal, but we were just becoming adults.

Things change. Attitudes change. Attachments change. We grow older, until we’re truly old. Soon, M and I will dig in and pare down. We’ve started a list of who gets what but were still in the planning stage. We may have one more move. I don’t even like to think about it, but if it happens it will be another downsize. And it will be the last stage of “decluttering” two complicated lives. We came into this world with nothing, and we’ll leave a little ash when we go. Zen Buddhism believes that attachment is a source of suffering. I can’t say I’ve ever suffered in that way though I’ve had plenty of attachments to people, experiences, and even material things. But I’m happy to let them go when I go, to pass them on to someone who might enjoy them as much as I do.

Here’s to George Carlin (RIP), Ann Patchett, Aunt Mary Alice (sorry about the Baccarat), and Marie Kondo, all of whom helped me think of my stuff and what it means in the scheme of things.