This is the “Low Country.” Before our recent trip through the “Old South,” I knew almost nothing about this 187 miles of South Carolina coastline with its barrier or Sea Islands. Traditionally, the phrase refers to the former slave holding areas where rice and indigo, both labor intensive crops that thrived in the hot, wet, sub-tropical climate, were the foundation of its economy. I’ve always had an affinity for the “big sky” vistas of the western high desert, but this astonishingly beautiful landscape with its long chartreuse-colored sea grasses, blue sky, live oak, Spanish moss, and tidewater is equally striking.

Charleston, with its well-preserved historic district and well-deserved reputation as a food lover’s destination, was our first stop, and since arriving we’ve marveled at its wonderful South of Broad mansions, enjoyed the tastes and flavors of the city, and the soft sibilant ya’lls of its residents. After four days of acclimation in the “Holy City,” our first true experience of antebellum life was a stop at Magnolia Plantation, an estate established in 1676 and still held in trust by descendants of the Drayton family, its original owners.

For nearly two centuries, the Draytons amassed great wealth through the cultivation of “Carolina Gold,” a special variety of rice, but following the Civil War, no longer able to rely on slave labor, the estate fell on hard times forcing the owners to sell three-fourths of their property and convert the plantation into a ceremonial garden.

The visit to Magnolia Plantation was not our first encounter with America’s slave owning past. In 2016, M and I spent three weeks visiting revolutionary and Civil War sites in Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia as well as the battlefield at Gettysburg. We both find it difficult to reconcile the natural beauty of these areas with the inhuman treatment of their formerly enslaved populations. In 1860, there were 4 million slaves in the United States, 400,000 of them in South Carolina. Magnolia Plantation “owned” 235. Today, Magnolia is public garden, but it is difficult to walk its grounds in the Carolina heat without feeling the suffering of its enslaved population.

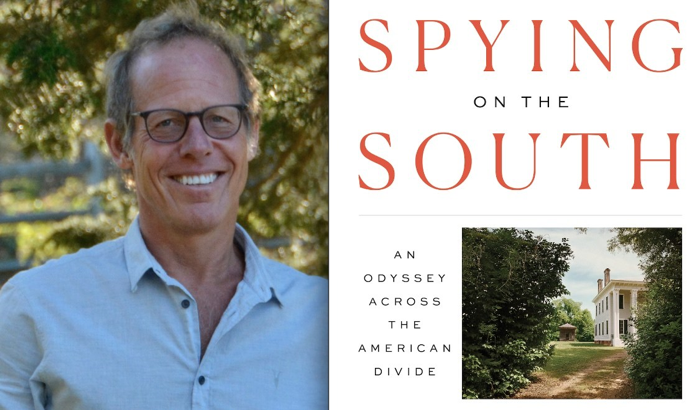

Our first real taste of today’s Low Country came as we approached Beaufort, a remarkably beautiful small city, that was our first layover on the trip south from Charleston. As we traveled through this landscape, we listened to two books on Audible – Pat Conroy’s South of Broad, a novel set in Charleston, and Tony Horwitz’s Spying on the South, a retracing of Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1850 journey through the South, looking at how things have or have not changed. Both books have added to our appreciation for the culture of the region pre and post-Civil War.

The South Carolina coast is dotted with barrier islands, from Edisto, Hunting, Lady’s, and Daufuskie (where Pat Conroy taught school for one year) and on to Port Royale and Hilton Head Island. The Low Country is nominally limited to the South Carolina coastal waterways, but the islands continue into Georgia with Saint Simons, Sea Island, and the Carnegie family’s Cumberland Island and on even further, into Florida, with the picturesque village of Fernandina on Amelia Island.

This is a breathtaking corner of America that few of us know well. It is well worth a visit, both for its beauty but also as a reminder of the nation’s checkered history. Wonderful antebellum homes stand in contrast to rows of slave quarters on those same estates. Charleston and Savannah are charmingly restored cities that reveal themselves as examples of America’s interest in historic preservation. Both were important in early America’s history, Charleston as a thriving port and Savannah as the center of its cotton-based economy, but both relied on enslaved people to build and maintain those elegant homes. I can’t help but remember that the 1994 bestseller Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil took place in Savannah and may be a suitable description of the region as a whole.

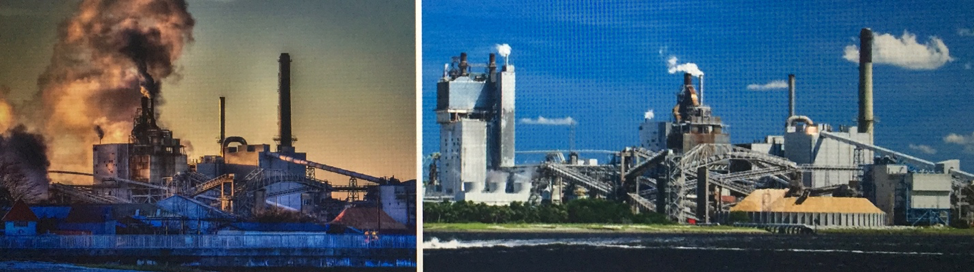

On Amelia Island the passage of time and its contrasts are especially noticeable. The island has a colorful history having been ruled over five centuries by eight different flags. In the 20th century it was the center of the shrimp fishing industry, but competition from overseas decimated the fleet, taking it down from over 100 boats to the three that call it home port today. Similarly, during the Great Depression the island was suffering from the economic devastation of the times but two giant companies, Kraft and Rayonier came to the rescue building enormous pulp mills, one to the east, producing fiber for cardboard, and one to the west making cellulous for use in making paper, clothing and plastics. Both plants produce smelly emissions and their unsightly industrial architecture dominates the otherwise beautiful Low Country landscape. The old town itself is quaint, well maintained, and from its streets the tourist is unaware of the industrial ugliness but leave the harbor on a river cruise and the two plants bracketing the town’s lovely historic center are a blight.

This is the “new south” struggling to establish a new identity. Communities rich in history are confronting the ugliness of a slave holding heritage, and others devastated by foreign competition seek to reinvent and recreate an economic infrastructure with good jobs that will sustain them. America’s current political divisions mirror the divide this historic region has always struggled to mask between the haves and have nots.

We have loved exploring this extraordinary landscape and learning its history. In 2016, we traveled in the Tidewater region of Maryland and Virginia, an area with an equally rich colonial history. We visited the homes of five American presidents – all slave owners. It’s clear to me from our travels now and then that America will forever be tarnished by the scar of its inhumane legacy. It is equally clear that America has made great strides in its effort to heal this wound. I can only hope the we continue the healing process and pull this divided nation together for our future.

** Footnote: Pulitzer Prize winner Tony Horwitz, the author of Spying on the South, died earlier this year, at age 60, while on a book tour promoting this book.