In early June my dad drove me up the dust-choking unpaved roads of rural Montana to meet the Mannix family and kick off my summer job as a ranch hand. When we arrived, introductions and small talk were made in the yard outside the house, and, though some big lightning scarred cottonwoods provided shade for the old two-story clapboard house with its screened-in porch, we were gathered near the car in the blazing hot sun.

I was 14 and my dad thought working on a ranch would be “good for me.” It was the life he knew growing up, and he wanted me to experience it too. I was never sure if his intention was to motivate me, punish me, or just find out if I had what it takes to survive, but I knew he thought we would both learn something if I spent a summer on a ranch.

As a kid, I was always uncomfortable with strangers, especially adults busy talking to each other while I stood awkwardly around. That day, as the adults talked in the hot Montana sun I shifted from foot to foot and wished the trickle of sweat would stop running down my side. I wanted them to stop and get on with it when the world started to spin, my vision narrowed, and everything went black.

When I came to, I was on the ground, covered with dirt, looking up at the adults. I don’t know who was more embarrassed, me, my father whose wimpy son had just passed out in front of strangers, my aunt who had gone to lengths to find me the job, or the Mannix family who were wondering what they were going to do with the city kid who had just fainted in their yard. Not exactly the kind of start any of us wanted.

The adults helped me up and everyone offered their explanations – too hot, needed water, no breakfast, etc. I sat on the bumper of the car, put my head between my knees, and sheepishly recovered. After a time, when they were satisfied that it wasn’t anything serious, my dad and Aunt Winnie left. In later years I wondered how my dad felt when he left me that morning? Was he mad? Sad? Relieved? Worried? I’ll never know, because he’s gone now and we never talked about it.

When he and Winnie were gone, Mrs. Mannix, with her white hair and flour covered apron, marched me to the room in the cookhouse I would share with Glen, their 17-year-old ranch hand.

I was a soft city kid, but Glen was the tough, self-reliant person I wanted to be. He’d grown up in the San Joaquin Valley of California and migrated to Montana with a set of practical skills acquired on his family’s small plot of land. He dropped out of high school but was a street-smart hard worker and a good teacher. He could have made my life miserable that summer but he didn’t. I suppose he was glad to have the company.

He was about my height but solidly built with a deeply tanned face and ropey veined forearms. He always wore the same thing – Levi’s, a pale blue work shirt with mother of pearl snap buttons, a Levi jacket if it was cold in the morning, scuffed high top shoes and the same straw “cowboy style” hat all of us wore to shade our faces from the blistering summer sun.

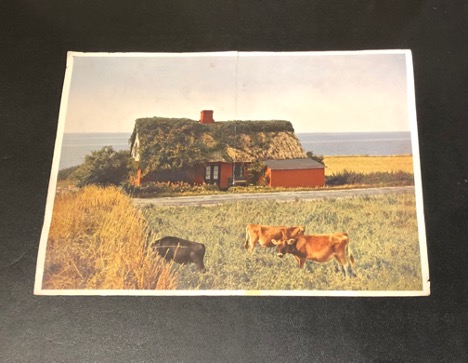

In those first days he taught me how to mount the family’s old stallion bareback then roundup and lead their three cows back to the barn. I learned how to milk them without having them step on my foot or kicking over the bucket before delivering the steamy warm milk to Mrs. Mannix and her kitchen crew. It wasn’t complicated, but he also taught me how to slop the pigs and feed the chickens and still get to the cookhouse by 6:30 in time for breakfast. My arrival was a good deal for him. These had been his chores before my arrival, and he got to sleep an extra half hour as long as I was there.

The real work of summer began in July with the start of haying season. I arrived in mid-June, so was able to learn a little about farm routine in the month before haying season began. I learned how to build fences and stretch barbed wire without ripping my skin to shreds and how to work on farm equipment without losing a finger. By the end of the first week my soft hands and heels were covered with big watery blisters and my face was crisp with sunburn.

In early summer Montana ranchers take their cattle up to pastures near the tree line where it’s cooler. One day in June, Glen and I rode up the treacherously steep hillside in the Mannix pick up to check and make sure they were OK. The pastures are high above the valley floor and coming back down we were bushwhacking through tall grass in the truck. I was clutching the door handle with one hand and the dashboard with the other because it felt like we were about to pitch forward over the hood. I saw then how competent and confident Bert was but also how vulnerable and close to the bone things were in that world.

When haying season arrived just after the 4th of July my education kicked up another notch. Not only were the days long and hard but so were the new faces that showed up. They were all white in those days. Mexican labor was a couple of decades away and much more reliable. These white transients were a new breed to me – indigent, nameless, and unpredictable – following the sun north as the crops ripened. There was an air of jaw-clenching danger about them. Mrs. Mannix confided that I was bunking with Glen in the cookhouse because it wasn’t safe for me to stay in the bunkhouse. For the next six weeks Glen and I lived across the corral from them but shared meals in the cookhouse with an ever-changing group of derelicts -unsavory, Muscatel drinking, Sterno-sipping, knife packing itinerants who performed backbreaking labor in the fields for $8 -10 a day. They ignored me, but I was fascinated by them.

Modern equipment and haying practices came late to the Helmville Valley. That was one of the last years that hay was still cut and raked with horse drawn equipment and stacked by hand. Now it’s baled or spun into giant rolls by mechanical balers. Back then, the family’s one concession to mechanized farming was a Rube Goldberg home-built contraption called a bull-rake adapted from a 1936 Buick and equipped with long wooden prongs protruding parallel to the ground in front. It chugged and sputtered through the fields lowering the prongs and picking up and rows of freshly cut hay to be delivered to the stacking area. I loved the smell of the fresh cut hay, especially in the morning. It still reminds me of summer when I smell it.

Once delivered to the stacking area the hay was loaded on a slanted panel called a “beaver-slide,” winched to the top, and dropped into a box made of moveable panels. If you were a “stacker” you stood inside the paneled area with a pitchfork and distributed the newly dumped hay evenly within the panels. Stacking paid more than the other jobs but it was also the dirtiest and hardest job. If you were in the stack you were covered with dust and seeds and barely breathable air.

In the beginning I operated the beaver-slide winch attached to the wheels of a pickup truck but I was greedy and wanted to be a stacker when I realized I could take home $2 more a day. The finished stacks were 12-15 feet high and there was no solid footing as they were going up. You stood inside the wooden frame and stomped around in the soft hay with a pitchfork trying to even it out. My second day as a stacker I drove one of the pitchfork’s tines through my boot and into my foot. Luckily, it came out as cleanly as it went in and didn’t cause any serious damage. I limped around for a few days but I was able to continue as a stacker.

When a stack was finished the stackers were winched down the beaver slide, the panels moved to another location, and a new stack started. I worked as a stacker for the last three weeks of haying season and when it was over I threw away all of my socks because no amount of washing could rid them of the burrs and seeds that worked their way into the knitted spaces and drove me to near madness.

Saturday night in ranch country is a true and abiding social ritual. It’s been extolled, lamented, sung about, and satirized in every conceivable way. In 1952 it was at the heart of my summer experience. On a ranch there is no such thing as a 40-hour workweek. Work is finished when it’s finished but, weather permitting, Sunday is a day of rest. When Saturday’s work is done it’s time to take a bath in a big, galvanized tub with hot water from the cookhouse stove and get ready for a night out. I had a clean pair of dark blue Levi 501’s and one soft cotton plaid shirt. That was my dress outfit. Saturday night was a breakaway event for ranch families and the college and high school kids who worked for them.

Glen, had a 10-year-old Chevy Coupe and Bert had a sleek new Mercury sedan with a vinyl roof – a classic of the day. Bert was only 10 years older, but that was a lifetime in those days. He also had a pretty, Helmville-raised, girlfriend named Darlene whom he married a couple of years later. He was a ruggedly handsome young rancher whose only concession to fashion was pair of Tony Lama ostrich boots and a light colored felt Stetson for the weekend. On Saturday night he would load Glen and me in the back of the Merc with Darlene in front and take us to town. We were on our own for getting home, but Saturday night in rural Montana is a group activity. There was always someone willing to round up the stragglers and take them home even though the houses were sometimes 10 or 15 miles apart.

The night always started with a movie, and it didn’t matter much what it was. There was no real theater in Helmville. The movie was shown in the church or Grange Hall, and when it came to “The End,” about 9, it was straight to the bar – the one and only bar in Helmville. It was long, narrow, and jammed with people. Some of the old timers had been drinking since late afternoon. The rest of us filed in after the movie and bellied up. That’s right; at 14 Glen and I were ordering drinks in a Montana bar. Jack and Glen’s Excellent Adventure. I was scared at first and sure something embarrassing would happen. I wasn’t sure what that might be but I knew I was tempting fate, and there might be a scene of some sort. It only happened once, when I asked the woman behind the bar for a Seven and Seven. She stopped what she was doing, put both hands on the bar, and looked at me with a smirky little smile. I backed away and she went back to work. I didn’t try it with her again, but I had a beer in my hand within a minute or two.

About 10 P.M. all fueled up, the ranch hands and college kids started looking for action. There was usually a dance somewhere in the area – Seeley Lake or Ovando were the closest towns big enough to draw a band and a crowd. Glen or one of the other young ranch hands would organize it, and we would pile into the cars and head off to the dance. Seeley Lake is 60 miles north of Helmville, a resort of sorts – primitive in those days – with a couple of bars, a few cabins, and rowboat rentals on the lake. But the bars were big enough to host a band and provide a small dance floor where we would stand around eyeing the local girls and nursing beers and until it was 1 or 2 A.M. and time to leave for home.

One night after an excursion to Seeley Lake, Glen was driving us back to the ranch in his old Chevy Coupe, a friend riding shotgun, and me zonked out on the narrow back seat, when suddenly I was tumbling around, bouncing off the front seat, then the roof, then back on the seat and around again with the air full of dust, empty beer bottles, a Copenhagen tin, and a loose screwdriver as we rolled over and over down a grassy hill. Then silence.

I was terrified I might be the only one not dead and wondering what I would do if that was true. It seemed like minutes but it was probably only 15 or 20 seconds, before someone asked, “Is everyone OK?” There was another pause and then two tentative “I think so” replies. When it sank in that everyone was OK and that no one was seriously hurt the three of us climbed out through the passenger side door, which was now sky side up. We all had bruises and small cuts, but there were no broken bones or worse.

Glen had been going too fast, started to drift on a gravelly corner, and caught a tire in a Montana pothole. The car flipped to the outside of the turn and down the grassy embankment. When we were all out of the car and had surveyed the wreckage, the three of us climbed back up the bank and when we were on the road looked down at the car whose headlights were two yellow spots pointed at the sky. We left the car. No police were called. A passing car picked us up and took us home. I don’t remember if Glen ever went back to claim the car. I sincerely believe the heavy steel and rigid frame of that old Chevy Coupe saved our lives. We had no seat belts or other protection, but cars were built of stronger materials in those days. Was it the steel, good luck or fate? That may have been the first of my nine lives.

The following morning, I got up and everything seemed like it was back to normal, I rounded up the milk cows and did the chores. At breakfast I didn’t look Mrs. Mannix in the eye for fear she would ask a question I didn’t want to answer about the bruises and the night before. In the afternoon Glen and I tossed a football around the yard, and on Monday morning we were back in the field putting up stacks.

At the end of August, it was over. My ranch adventure at an end. It was bittersweet. I hated to say goodbye, especially to Glen, but I was looking forward to seeing my friends at home. Aunt Winnie came up from Deer Lodge to retrieve me. We stopped at the Drummond Rodeo on the way home. It was her gift and a fitting way to close out my Montana summer.

_____

Fast forward to today…

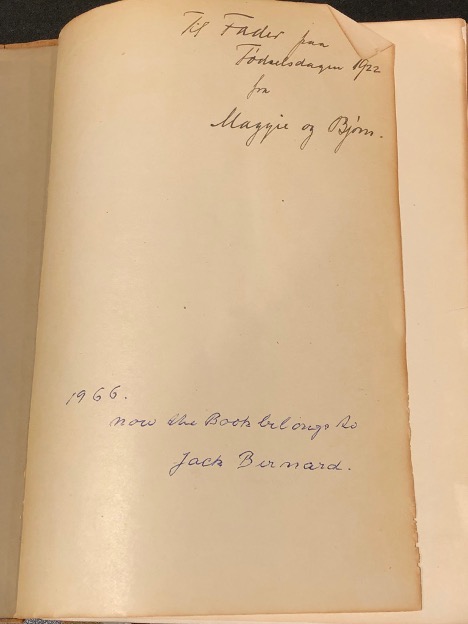

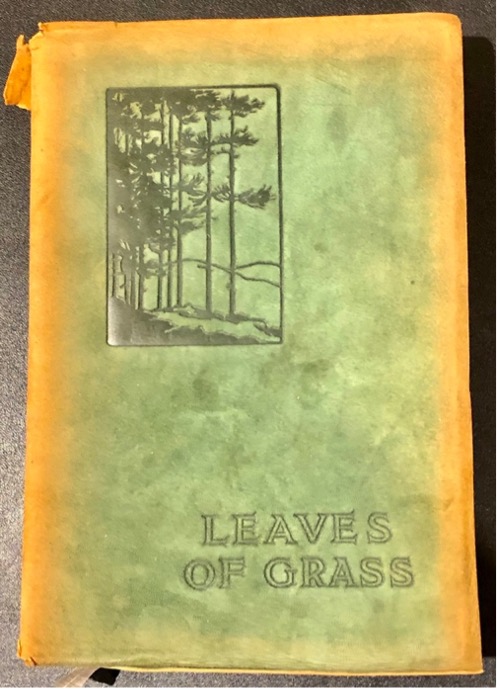

I’ve always been proud of my Montana roots and maintained a connection there. My mom was born in Missoula and so was I. She attended school with Norman Maclean, the author of A River Runs Through It, and his brother Paul, the tragic sibling in the novel. Both of my parents graduated from the University of Montana and so did my daughter, Diana, and son-in-law Nick. My oldest son, Brent, graduated from Montana State in Bozeman and grandson, Will, started as a freshman at U of M last year. Four generations of Bernards rooted in western Montana soil.

A few years ago, I took Marilynn back to see Helmville, the Mannix ranch, Seeley Lake, and old Missoula. I went to the one-person Helmville Post Office and asked about the Mannix family. Yes, they were still there, she told me, and the ranch was bigger than ever. What was 8000 acres when I worked there is now 18,000 deeded and 30,000 leased acres. This is a big cattle and timber operation.

On our return to Seattle, I wrote the Mannix family asking about the members I knew back in the day. In return, I received a handwritten letter from Darlene. Bert, unfortunately, died a couple of years ago but Glen, my roommate, is still alive and lives nearby. Bert and Darlene’s three sons and their wives run the ranch now while Darlene enjoys her role as great-grandmother-in-chief.

Recently, I’ve been in touch with Logan Mannix, one of the fifth-generation, the next in line to take over. His curiosity and our back and forth has made me feel I’m part of their extended family. My summer in Helmville was a rite of passage, and it feels important to stay connected to the Mannix family.

The circle of life continues… because this winter my 18 year-old grandson, Will Price, is working on a ranch in Patagonia. I’m hoping his ranch experience is as memorable and satisfying as mine was 68 years ago in Helmville.