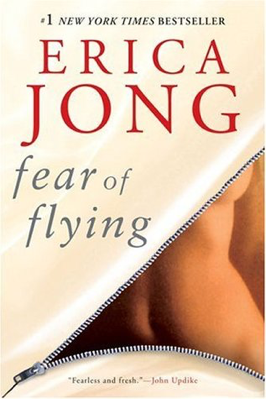

In Erica Jong’s 1973 novel, Fear of Flying, we were introduced to the “zipless fuck,” a sexual encounter involving two previously unacquainted persons with no emotional commitment.

In Erica Jong’s 1973 novel, Fear of Flying, we were introduced to the “zipless fuck,” a sexual encounter involving two previously unacquainted persons with no emotional commitment.

In Grounded, a play by George Brant, a young woman in an Air Force flight suit tracks a terrorist on the ground 8000 miles away. She’s “flying” a missile-armed drone from her air-conditioned trailer in the Nevada desert. She is prosecuting America’s zipless war.

As an ex-Marine fighter pilot, I resist the conflation of jet pilot and drone operator. Real fighter pilots strap in, light the fire, pull G’s, land on aircraft carriers, and swap sea stories in the Ready Room. In Grounded, the unnamed pilot feels the same way. She’s a hard charging, adrenaline-fueled F-16 driver, but following maternity leave she finds herself assigned as a UAV (unmanned air vehicle) “pilot” in a windowless trailer in the Nevada desert. She is not happy with the assignment. She misses the excitement. She misses “the blue,” but war is changing and she has to deal with it.

Creech Air Force Base is the home of the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Battlelab. It sits forty-five minutes northwest of the Las Vegas Strip, in the middle of the desert, where real “pilots” flying unmanned drones reconnoiter the battlefields of Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, and Syria and track dangerous insurgents who use these remote locations to evade their enemies.

Today the Air Force has more unmanned drones than manned aircraft in its arsenal. Its use of drones has increased exponentially since America’s wars in the Middle East began 15 years ago. According to Grégoire Chamayou in his 2013 book, A Theory of the Drone, the number of patrols by American armed drones increased by 1200% from 2004 to 2011.

Drone piloting is the ultimate video game, and the Air Force is now acknowledging that it doesn’t take an F-16 pilot to fly one. Today’s cadre of drone pilots now includes rigorously screened enlisted men and women as well as combat trained pilots. It takes two years and $2,600,000 to train a fighter pilot but only ten weeks and $175,000 to train a drone pilot. You do the math.

Nevertheless, despite the fact that “the threat of death has been removed” unmanned vehicle pilots have a surprisingly high burnout rate. Long boring days in a darkened trailer looking at a computer screen has its downside. Pilots have always said their lives are filled with hours of boredom interspersed with moments of stark terror, and while physical danger is missing in that trailer, the job exacts its own emotional toll.

Grounded is only one of several stage and film treatments of the subject. In the film Good Kill (2014) Ethan Hawke plays a drone pilot who questions the ethics of firing missiles in Afghanistan from his trailer in the Nevada desert, and last year (2016) Helen Mirren and Alan Rickman posed similar ethical questions about civilian casualties, chain of command, personal responsibility and other political questions relative to drone warfare in Eye in the Sky.

In the play, our earth-bound “pilot,” though disappointed by her new assignment at first, makes peace with it and takes comfort in living “normally” with her husband and child in Las Vegas. She reminds us again and again that “the threat of death has been removed.” She finds it comforting but ultimately unsatisfying. Soon, life in “the Chair Force” starts to wear her down. She can’t talk to her husband about her work and finds herself unable to isolate the two lives. She begins to humanize the images she sees on her computer screen. Ultimately, like Eye in the Sky, it is a child that causes her ultimate breakdown. She imagines her own child in the crosshairs on her screen.

In a discussion with friends after the play I confessed to having misgivings over the fact that the playwright cast a woman as the pilot. Artistically it works. Mahria Zook, the actress, owned the stage and our attention for 90 minutes without an intermission, displaying a range of emotions from joy to anger to disappointment and ultimately to madness. She was exhausting and impressive.

So what is my problem? I have a feeling that casting a woman in the role made it easier for the audience to relate to the character’s emotional turbulence. Is it because I think women are more emotional? Is it because I believe women are weaker? I don’t think so, but I can’t be sure. All I know is that I was a little distracted and thought the playwright was giving us an easier emotional connection. It would surely have been a different play with a man in the role. Not better, just different.

My experience may be sexist. When I was flying F8’s and A4’s there were no women fighter pilots, and I may have some unacknowledged prejudice about a woman’s ability to yank and crank with the boys. My friend, Bob Gandt, wrote a profile of the Navy’s first woman F-18 pilot and the controversy surrounding her qualifications and eventual death on a carrier approach in his book Bogeys and Bandits. That was 24 years ago. I don’t know the status of women fighter pilots today. Like all pioneers, the first women were deer in the headlights. I hope the culture has changed, but in a testosterone-fueled Ready Room, preparing for a catapult launch, there are bound to be some unreconstructed good old boys.

In the same way that Erica Jong’s zipless fuck wasn’t really free of emotional content, the real life UAV pilots in the Nevada desert often feel conflicted as human targets appear in real life situations – family gatherings, strangers in field of fire, children playing in the street – as they prepare to launch a missile. In a world where young people grow up playing video games, controlling missile-armed drones is the pinnacle – but as the play and movies reveal this game is fraught with moral questions and emotional ups and downs.

The next time you’re looking for spellbinding entertainment, check out Eye in the Sky or Good Kill, good films that explore the moral, psychological, and political implications of our zipless war. If you’re lucky you might find even find a local production of Grounded and experience those feelings in a live theater performance.

Art does illuminate.

(Special thanks to Sara Keats, the dramaturg at SPT, for some of this information)